Exploring the Hidden Earth-Like Worlds in Binary Star Systems

Written on

Chapter 1: The Search for Habitable Exoplanets

Earth stands out in our solar system as a unique celestial body, being one of the few with an atmosphere and the only known planet that supports life. But how many more planets like Earth could exist beyond our own? Recent studies indicate that we may be overlooking a significant number of Earth-like exoplanets in binary star systems, which could enhance the likelihood of discovering habitable worlds.

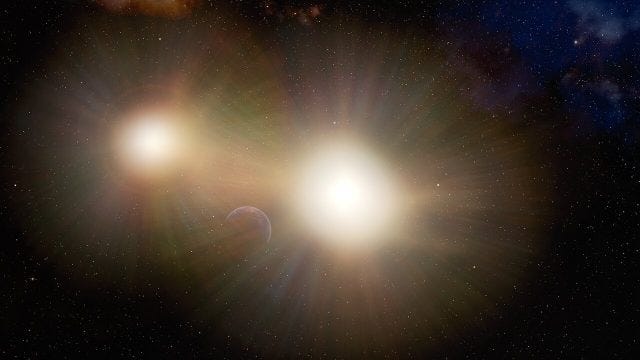

Despite orbiting a single star, we are surrounded by numerous multi-star systems. Estimates suggest that roughly one-third to possibly half of the solar systems within the Milky Way consist of two or more stars. When stars are positioned closely together and sufficiently distant from us, they may appear as a single light source through telescopes. This phenomenon can complicate the search for planets.

Currently, astronomers have confirmed over 4,000 exoplanets, with most being larger than Earth. This trend arises from our detection methods, as direct imaging of exoplanets is often beyond our capabilities. Instead, scientists utilize various techniques, such as gravitational effects and light variations, to identify these distant worlds. The transit method, predominantly used by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), proves to be the most effective. This method involves monitoring light dips as planets pass in front of their host stars, similar to how Kepler discovered thousands of potential exoplanets.

NASA's Ames Research Center team utilized the Gemini North and South telescopes in Chile and Hawaii to investigate nearby TESS targets for potential binary systems. Their observations revealed that 73 of these stars were indeed binary pairs. They also employed the WIYN 3.5-meter telescope to analyze 18 additional known binary systems identified by TESS. Interestingly, while TESS discovered both large and small Earth-like exoplanets around single stars, it only identified large gas giants within binary systems.

The nearby Centauri system exemplifies a well-known multi-star arrangement, with Alpha Centauri AB on one side and Proxima Centauri positioned at the center of the red circle. This research implies that Earth-like exoplanets may be concealed within binary systems, eluding detection due to the limitations of our current methods. As study lead Katie Lester points out, smaller planets are likely to be lost in the brightness of a binary system, making their transits difficult to track accurately.

This finding adds complexity to the field of astronomy. As long as the transit method remains our primary means of cataloging exoplanets, researchers must carefully consider whether a system is binary. If so, we may not have a complete understanding of the planetary population, potentially indicating a far greater number of Earth-like planets than previously thought. Somewhere in the universe, perhaps a being gazes up at dual stars, pondering the possibility of life evolving under such conditions.

The first video, "Binary Stars Could Stabilize Planets to Be Habitable!", discusses how binary stars may create stable environments for planets, enhancing the potential for habitability.

The second video, "New Weird Planets - Binary Star - Kepler - Science at NASA," delves into the fascinating discoveries of unusual planets within binary star systems, showcasing the ongoing research in this area.

Chapter 2: Implications for Exoplanet Research

In light of these findings, it’s clear that our understanding of exoplanets must evolve. The prevalence of binary stars suggests that many Earth-like worlds could be hiding in plain sight, waiting for our detection methods to catch up.