Exploring the Complex Relationship Between Blood Sugar and Hunger

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Hunger and Blood Sugar Levels

Is Hunger Linked to Blood Sugar Drops? A Scientific Inquiry

A recent international study sought to clarify the relationship between hunger and glucose response following meals. Experts in appetite research revisited the "glucostatic hypothesis," initially proposed by Dr. Mayer in 1953. This theory posits that low blood sugar levels trigger feelings of hunger and lead to food-seeking behavior.

Despite numerous hypotheses on appetite regulation, none have fully explained the phenomenon of hunger. The findings from this latest study indicate that fluctuations in blood sugar levels are indeed associated with hunger. In this article, I will share my own experiences with blood sugar changes post-meal, explain the study's methodology, and discuss its key findings. My aim is to illustrate that the connection between blood sugar and hunger is more intricate than it appears.

How Blood Sugar Levels Change After Eating

For healthy individuals without diabetes, fasting blood sugar levels should typically range between 4.0 and 5.6 mmol/L. The American Diabetes Association defines levels above 5.6 mmol/L as pre-diabetes and those exceeding 7.0 mmol/L as diabetes.

After consuming a meal rich in carbohydrates, blood sugar levels peak approximately 30 minutes later, followed by a gradual decline back to fasting levels. At times, this drop may dip below fasting levels, resulting in a "blood sugar dip."

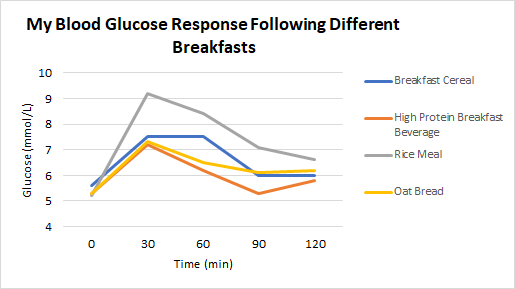

Below is a real-life example of how my blood sugar responded to various breakfast options:

The graph illustrates my blood glucose levels after different breakfasts, measured using the fingerstick method. Each breakfast varied in calorie content, with the cereal, rice meal, and oat bread each containing 50g of carbohydrates. In contrast, the high-protein breakfast beverage contained around 20g of carbohydrates. Notably, only the high-protein beverage caused my blood sugar to drop below fasting levels within two hours.

Study Methodology and Findings

This study involved a larger exploratory cohort of 1,000 participants in the UK and a smaller validation cohort of 100 participants in the US. Participants consumed standardized breakfasts with varying macronutrient compositions over 13 days, including a 75-gram glucose drink test (Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, OGTT). After consuming these meals, participants waited three hours before eating again.

Blood sugar levels were monitored continuously via a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM), which recorded levels every five minutes without the need for frequent skin pricks. Participants also rated their hunger on a scale from 0 to 10 and logged their food intake using a mobile app.

The researchers discovered that blood sugar dips—specifically, levels falling below fasting states—were correlated with feelings of hunger and the initiation of subsequent meals. The strongest correlation was noted after the glucose drink test, where rapid spikes and drops in blood sugar occurred. This suggests that if blood sugar rises and falls too quickly after consuming high-sugar drinks, individuals may experience a strong urge to eat when their blood sugar dips.

Evaluating the Link Between Blood Sugar and Hunger

While the correlation between blood sugar dips and hunger was statistically significant in the larger UK cohort, it became insignificant in the smaller US group. This raises questions about the robustness of the findings; ideally, a strong effect should yield consistent results across different populations.

Interestingly, blood sugar levels only accounted for less than 5% of the total variance in hunger, indicating that they are not a reliable indicator of hunger.

Implications for Diabetic and Pre-Diabetic Populations

The study primarily focused on healthy participants, leaving unanswered questions regarding individuals with pre-diabetes or diabetes, who typically maintain higher blood sugar levels for extended periods. These individuals tend to consume as much food as their healthy counterparts, despite elevated blood sugar levels, which challenges the glucostatic hypothesis.

The Impact of Eating Patterns on Blood Sugar

The study's design required participants to consume standardized meals in a single sitting, neglecting the common eating habits of many individuals who may snack throughout the day. As Dr. Panda noted in his research published in Cell Metabolism, "Human eating lacks a three-meals-a-day structure." This suggests that frequent snacking may prevent blood sugar from dipping below fasting levels.

Concluding Thoughts

While the study reveals a statistically significant connection between blood sugar dips and hunger, it's important to recognize the limitations of the findings, particularly the weak correlation in smaller cohorts. This research underscores the complexity of appetite regulation and highlights the need for a deeper understanding of the biological mechanisms at play in various real-life scenarios.

I remain curious about the impact of blood sugar fluctuations on hunger and the broader implications for appetite regulation. Thank you for reading! If you found this article insightful, you might also enjoy related content on appetite regulation:

Three Phases of Appetite Regulation and the Challenges to Effective Control

Understanding how appetite functions may aid in developing strategies to manage it effectively.

Chapter 2: The Role of Blood Sugar in Appetite Control

This video explores why some individuals feel hungry all the time, featuring insights from Dr. Ana Valdes and Dr. Will Bulsiewicz.

In this concise video, the effects of foods, medications, and stress on blood sugar levels are explained, providing a deeper understanding of appetite regulation.