The Complexity of Understanding: Carl Sagan's Misstep

Written on

Chapter 1: The Pitfalls of Reductive Explanations

In scientific discourse, it's crucial to steer clear of reductive explanations whenever possible, as they create a misleading sense of understanding.

Here’s a well-known reaction GIF that encapsulates this idea.

To provide some context, Carl Sagan was visiting his old sixth-grade classroom, engaging students with discussions about space. When a student inquired, “Why is the Earth round instead of some other shape?” Sagan's enthusiastic response was well-received, though somewhat misguided.

His explanation was centered on gravity. He stated that Earth possesses significant gravitational force, which causes any large protrusions—like mountains—to eventually succumb to their own weight. In his words, gravity pulls all mass toward the center, thus rounding out larger objects. He then noted that smaller bodies, with their minimal gravitational pull, can take on various shapes.

However, I find several flaws in this response. For starters, why hasn’t Mount Everest collapsed under its weight? Weighing approximately 357 trillion pounds, Everest is indeed massive, but what constitutes a “really” large bump? While erosion primarily shapes Everest, gravity does play a role.

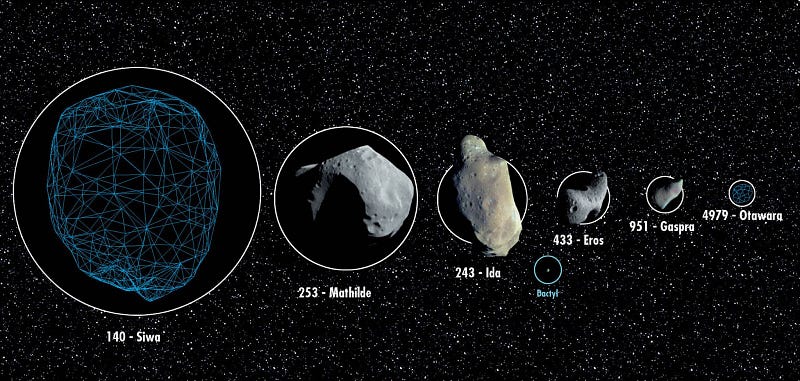

Next, Sagan referenced non-spherical asteroids that lack sufficient gravity to become round. While gravity influences their shape, it’s not the sole factor. For instance, a droplet of water in microgravity forms a sphere due to surface tension, which seeks to minimize its surface area.

While Carl Sagan was undoubtedly a masterful communicator, his eagerness to provide a simple answer led him into reductive territory. This kind of explanation can create a façade of comprehension, which is something we should strive to avoid.

Section 1.1: The Allure of Simplified Explanations

Reductive answers have a strong appeal as they promise a quick understanding of complex topics. For example, when discussing why the Earth is round, the common reductive response is to attribute it to gravity, implying that any irregularities are "squashed" into a spherical shape. Alternatively, one might mention potential energy minimization, asserting that spheres represent the lowest potential energy configuration for celestial objects.

Though these explanations hold some truth, they do not capture the full picture. Gravity certainly contributes to the shaping of celestial bodies, but it fails to clarify why small objects, like water droplets, maintain a spherical shape or why many larger asteroids are not round. This limitation exemplifies the primary flaw of reductive explanations—they offer an illusory comfort, presenting a universally applicable causal mechanism that falls short in more complex scenarios.

Section 1.2: Infinite Regress and Misleading Certainty

Reductive explanations can also lead to infinite regress—an unending search for fundamental causes. If we assert that gravity shapes Earth into a spherical form, one might then ask why gravity behaves as it does. This could open a Pandora's box of further questions about mass and space-time, each demanding its own explanation. While this exploration can be intellectually stimulating, it often fails to provide a comprehensive understanding for the general public.

When not interactive, reductive explanations risk being interpreted as definitive truths. They carry an authoritative tone that can mislead audiences, suggesting a complete understanding of complex scientific phenomena when, in fact, our knowledge is often evolving. This oversimplification can create a false sense of comprehension, discouraging deeper inquiry and critical thinking.

Chapter 2: The Importance of Nuanced Understanding

Sagan’s response suggests a singular reason behind Earth's shape, while scientific phenomena are typically the result of many interacting forces. Presenting a single cause as the definitive explanation fosters a skewed view of science as a field with clear-cut answers rather than one characterized by intricate, interconnected systems.

By fostering an illusion of understanding, reductive explanations not only misrepresent the complexity of natural phenomena but also undermine the crucial educational goal of nurturing an inquisitive and informed public. This reliance on oversimplification can impede public engagement with science. When people expect easy answers, they may feel disillusioned or disengaged when faced with the genuine complexities of scientific inquiry, leading to skepticism and diminished scientific literacy.

Subsection 2.1: Embracing Complexity

Rather than seeking simplistic responses, we can reframe our inquiries to embrace complexity. Instead of questioning why planets are spherical, we could ask, “Why wouldn’t something be a sphere?” In the absence of other factors, the default assumption should be symmetry. A sphere represents the most symmetrical form in three dimensions, prompting us to seek explanations for any deviations from this norm.

Sagan's focus on how gravity pulls objects into spherical shapes overlooks a more nuanced perspective. A more elegant inquiry might involve exploring what prevents roundness, leading to considerations of various factors—like the material characteristics that differentiate liquids from solids, thus explaining why water can easily form a sphere while Everest cannot. Furthermore, external factors like collisions that shape asteroids introduce clear asymmetries worth investigating.

Such a shift in thinking mirrors the scientific process itself—challenging assumptions propels our understanding of the universe forward. Instead of merely providing answers, we should prioritize asking better questions, which leads to richer exploration and a more accurate grasp of how things function.

So, why is Earth round? Because, in the absence of other information, roundness is the expectation. If it were not round, that would warrant investigation. In fact, the Earth is not a perfect sphere but rather an ellipsoid—an intriguing complexity to explore.

Navigating the delicate balance between accessibility and oversimplification in scientific communication is challenging. The quest to distill complex concepts into digestible explanations without sacrificing their richness requires both creativity and restraint. In critiquing reductive responses, we must also acknowledge the difficulties that alternative approaches present. Striving for this balance honors the legacy of communicators like Carl Sagan, whose efforts to ignite curiosity have motivated countless individuals. Ultimately, our goal should not merely be to convey information through definitive answers but to cultivate a deeper engagement with the mysteries of the universe by refining our ability to ask profound “why” questions.